Sara Gonzalez

The people and the sea: Towards sustainable management of Chilean kelp forests

-

Project Proposal

In Chile, harvesting kelp provides a livelihood for many coastal populations, but also threatens marine life with habitat loss. I propose to: 1) conduct fieldwork with local researchers at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile’s coastal field station to assess the effect of kelp harvesting on fish and invertebrates, 2) take marine biology courses at the university, and 3) interview key stakeholders (in Spanish) involved in kelp harvesting.

Beyond scientific engagement, I will engage with the community via interviews related to my research and interactions with university students. At kelp removal sites, I will interview residents, tourists, and fishermen about their perspectives on species conservation and the relationship between the coastal environment and their own lives. While studying at the university, I want to socialize with students outside of class and learn about their cultures.

Upon returning to the United States, I plan to enroll in a PhD program and apply my broadened understanding of scientific knowledge, perspectives gained from interacting with researchers and laypeople alike, and the research skills and international connections I will have fostered through my Fulbright experience. I intend to focus my PhD research on marine ecosystem conservation issues and later pursue a career as an ecologist.

Final Report

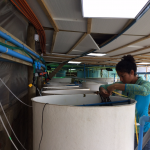

I conducted my research at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile’s Estación Costera de Investigaciones Marinas in Las Cruces, Valparaiso (V) Region, Chile. I was able to take part in three projects during my program: 1) participate in an ongoing study on the ecological effects of subtidal kelp harvesting; 2) conduct interviews with fishermen in various regions about their kelp harvesting practices and perceptions of the resource; 3) design and conduct a laboratory experiment to examine the potential effects of fish-derived nitrogen on kelp growth. The university’s marine lab had excellent laboratory facilities and field equipment. I worked with multiple principal investigators, post docs, graduate students, and technicians at the marine lab, all of whom were integral in making my project a success. When I needed additional resources, such as lab materials or expert consultation on a research topic, I reached out to other professors at the Católica or other universities. Through my interviews with fishermen, I formed new contacts with people at the fishermen coves and the Servicio Nacional de Pesca y Acuicultura.

I learned of my host professor by happening upon one of her publications as I was reading marine ecology papers on research done in Latin America. I sent her an email and be began to communicate about her current projects and my interests, and we found a lot of overlap. We continued to chat via email and Skype throughout the application process and prior to my arrival in Chile. When I arrived at the university marine lab, I had the opportunity to collaborate with and learn from other professors as well. We maintained a good professional relationship and will continue to build on the research that I accomplished during my grant period.

I would advise future grantees to always be conscious of your personal timeline for your project and maintain good communication with host affiliates when working through research challenges. Professors are often very busy, and nine months may seem like a long time, but the time will fly by and you don’t want to be hindered by delays that could have been avoided with a little persistence. In the same vein, don’t be shy about seeking support from others within or outside of your university (while maintaining open communication with your host professor). For overcoming language challenges, I recommend finding a friend or two who don’t mind taking the time to explain the numerous Chilean slangs that are widely used, and who will pause in conversation to clarify something when you don’t understand.

-

Proposal:

Final Presentation:

-